Being There First

Accidents of history have placed us in the elite ranks of Montana’s most venerable white families.

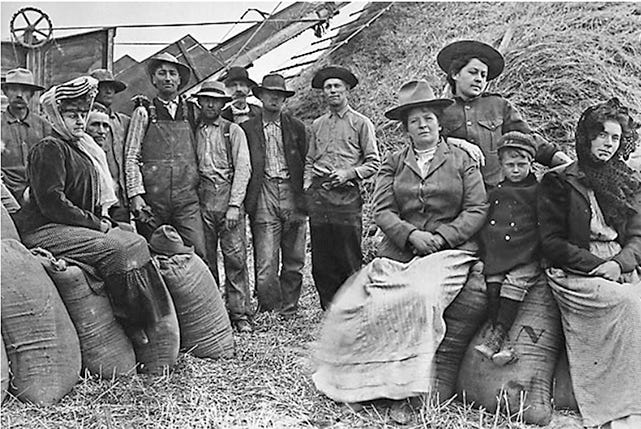

Because I was raised in a building that previously sheltered turkeys, the news that I was actually a blueblood came as quite a shock. No, I can’t trace my people to the Bourbons, the House of Tudor, the Kennedy’s or even the Osmonds. But it is a fact that in 1866 my great-grandfather, trembling with greed, joined a rush of equally foul-smelling fools who galloped off in the dead of winter from Last Chance Gulch in what is now Helena, Montana to the Sun River Country—where Charles M. Russell would set his paintings of cowboys and Indians—after some frontier wit spread a bogus rumor of gold. The date of the Sun River Stampede is important because it establishes that old Thomas Moran had set up housekeeping before 1869 in what would become the Treasure State. And that accident of history qualified me to join our premier organization of vintage names—the Sons and Daughters of Montana Pioneers.

As the date of my induction in Helena approached I got a little bit jumpy. First, would the other Sons and Daughters be snooty? After all, although Thomas possessed determination and courage, he wasn’t exactly a fine gentleman. Before he made his way to Montana he had fled Ireland, was rejected for service in the Civil War, and sailed off in a snit to San Francisco, where he milked cows for a living.

But Kitty, my wife, reminded me that most of the citizens who founded this high, wide and handsome place were also scum. In fact, she and her four sisters, who had likewise been accepted into the Pioneers, claimed as their legacy a tyrant who built an empire of cattle and sheep by attacking his neighbors with guns and lawyers but lost his fortune because he couldn’t stop getting married.

But my other anxiety was more vexing. The keynote speaker would be Stephen Ambrose, the best-selling author of Band of Brothers and Undaunted Courage, a history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. I had just published an article in a Outside magazine about a long journey of my own, playing golf and drinking vodka along the Lewis and Clark Trail from Great Falls to St. Charles, Missouri. To say that my account was not an academic treatment would be kind. In it, for example, I had described the explorers as carnivorous, murderous barbarians, and deduced that Meriweather Lewis was a homosexual who’d been having an affair with Peter Cruzatte, one of his men, both of whom were deeply into leather. I had further hypothesized that when Cruzatte shot Lewis in the butt during an elk hunt in North Dakota the assault had been intentional, the result of a lovers’ spat, and not accidental, as Lewis had claimed.

Still, I couldn’t be certain that Ambrose had read this hare-brained literature. But when we got to the dinner and saw the distinguished historian in bifocals and an angry red tie poring over his notes at the head table, my stomach sank. I began to imagine the vocabulary with which he would roast my eccentric scholarship, and how the Pioneers would rise, fingers pointing me to the door, eyes burning like those of Red Sox fans the night Bill Buckner let that grounder hop between his legs. Kitty patted my hand and ordered a beer. A gang of bushy-faced men in buckskin and fur filed through the door to honor the explorers with a loud rendition of a song from the period called “The Lowering Day.” Then they sat down at a table together to gorge themselves on beef.

Two hours later, long after the dessert plates were cleared, the officers of the Pioneers were still giving each other awards and eulogizing dead comrades. Ambrose looked like he’d been trapped in night court. The speaker began announcing the organization’s 70 new members. As she called out my name I slouched in my chair and pretended that the program was the most riveting prose I’d ever read.

When he was finally introduced Ambrose stared right at me and launched into a story in a gruff, overused voice about how a twenty-something T-shirt clerk in the mall where he had signed copies of his book that day asked him who Lewis and Clark were.

“‘You graduated from high school in Montana and you don’t know Lewis and Clark?’” Ambrose growled, a mimic of himself.

“‘Well, I’ve, you know, heard the names?” he warbled in falsetto. “But, like, when were they?’”

I pushed myself lower in my chair. At the next table one of the senior Pioneers, head down, hands on his glutinous American belly, was already nodding off. He dropped into a deep coma when Ambrose began describing two chapters of the book his publisher had axed. They dealt with the tribes who helped the Corps of Discovery through its first winter and over the Rockies.

“Without the Mandans and the Nez Perce Lewis and Clark might never have seen the Pacific,” he said, looking out at us. There was not, of course, a single Native American face looking back. “The Canadians would have armed the Blackfeet. And none of you would be here.”

It was a terrific speech. The applause even woke up our dozing Pioneer. But I wasn’t about to give Ambrose another chance to nail me in front of this partisan crowd. When the applause died and a blonde got up to sing God Bless America, accompanied by a boombox instrumental in what sounded like a whole other key, I took Kitty by the elbow. Clutching our little blue Montana Pioneer ribbons, we slipped out into the hot, starless night and went looking for a martini.